Common problems with bought footwear

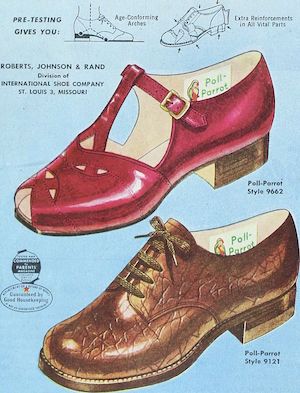

These shoes were marketed for boys and girls in 1948. Both have a considerable heel as well as noticeable toe taper. But fear not, the styles were commended by parents! Imagine what kinds of foot injury the wearers of these shoes have today.

Below, I outline six ways that modern shoes fail to fit our feet, and discuss some of the reasons why it’s hard to buy footwear that bucks the trend.

This isn’t meant to be an exhaustive academic treatise, it’s simply some of my thoughts, published here in case it helps someone else work out how to find better footwear in the face of the siren call of fashion.

After all, we won’t see change unless we start creating it. If more people were aware of how footwear can damage feet, there would be more of a market to cater for. We would all benefit from that.

Problem 1. Same-size shoes vs different sized feet

When we buy a pair of shoes, we buy a particular size: men’s 9, or women’s 10, or EU 41. Both shoes in the pair are the same length and width.

But real people often have different sized feet. My spouse has one foot that’s half a size longer than the other. My feet are the same length, but one foot is 4mm wider than the other. We are not unusual in these discrepancies. Like many other people, we find that if one shoe in a pair fits well, the other is too tight or too loose.

If we were wealthy enough, we could pay to have a shoemaker craft shoes to fit each foot exactly. But not many people can afford to employ a custom shoemaker, especially when every pair of shoes, boots and sandals would need to be custom made. Most of us need to buy mass-produced shoes, and mass production does not currently lend itself to letting consumers buy a pair of shoes consisting of two different sizes.

Maybe it will become easier to buy different-sized shoes if new manufacturing techniques are developed. For example, it’s becoming cheaper and easier to 3D print footwear. If one is printing shoes, maybe it will become possible to allow a pair to consist of different shapes and sizes to suit our differently shaped and sized feet.

Problem 2. Tapering, symmetrical shoes vs asymmetrical feet

If you look at a pair of shoes bought in a store, chances are that its toe area looks fairly symmetrically tapered around a line drawn centrally through the length of the shoe. The taper starts at roughly the ball of the foot, and is often the same on the inside of the foot as on the outside. Most styles, by most footwear brands, have toe shapes that taper significantly.

Why does toe taper in footwear matter? Look at your foot when you are barefoot. If you are more than a couple of decades old, look at a young child’s foot instead, because your own foot will almost certainly be deformed already by years of wearing pointy shoes:

- the natural human foot is strongly asymmetric

- the toes spread out to occupy an area that’s as wide as (or even wider than) the ball of the foot

- the bones in the toe on one side of the joint line up with the bone in the midfoot on the other side of the joint.

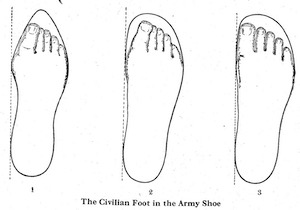

The deforming effect of footwear has been well known for centuries. Here is an illustration from a military manual published in 1918 for officers in World War I, showing how men’s feet accustomed to pointy civilian shoes (left) may eventually spread when wearing foot-shaped army boots (right). Recruits’ deformed feet posed a real issue of fitness for combat.

The pointier the toe shape of the shoe, the more the toes will be pulled out of their natural alignment. Any kind of taper means the big toe is pulled towards the center line of the foot. Eventually, after months or years, feet can develop bunions, crooked toes, nerve damage, plantar fasciosis, sesamoiditis, and other symptoms of long-lasting damage. Ouch! Some of this happened to me, and I can attest that it has been no fun at all.

The damage caused to feet by pointy-toed footwear has been known for at least 150 years, and probably for far longer. Even today, women in western cultures are more likely to develop bunions and hammer toes than men: no surprise when we consider that women’s styles are typically much pointier, with higher heels that put extra stress on joints. Yet fashionable shoes for men and women continue to have tapering toes. Even children’s shoes usually have visible tapering.

Toe shapes that are best for our feet let our toes move naturally: they are as wide or wider across the toes as they are at the ball of the foot, and they are asymmetric, with enough space for all the toes to move without being constrained.

However, very few shoe and boot styles that one can buy have this shape. Instead, toe shapes of most purchased styles taper fairly symmetrically around the foot center line. Why is this? I have a few theories, which are not mutually exclusive

It’s easier to get footwear with tapering toes off a last

If the toe shape is wider than the ball of the foot, it can be difficult to pull the finished shoe off a last without damage. This is not true for all shoe styles, but for enough of them to be an issue.

Mass manufacturing of footwear typically requires lasts. To maximize the number of styles a factory can produce, and to minimize the time and wastage per pair (especially if labor is less skilled, to reduce costs), lasts need to taper enough to let shoes be pulled off easily.

In fact, I found it impossible to buy off-the-shelf lasts that weren’t tapered around the center-line of the foot: I had to have my asymmetrically-shaped lasts custom made. These days, it is easier to buy non-custom lasts with wide toes, but they are still few and far between.

This handmade British shoe from the 16th century has a very practical toe shape for a working person: the toes can spread out as they would in a foot without shoes, allowing the joints to work well to support the loads put on them. It also had a completely flat, heel-less sole (Shoes are in the Bashford Dean Memorial Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York).

It’s easier to design symmetrical patterns than asymmetrical ones

The more asymmetrical the shoe shape, the less match between the pattern for the inside of the shoe and that for the outside of the shoe, at least if the shoe is close-fitting. Designing a good-looking pattern therefore takes longer and requires more expertise.

In an age when shoe styles last just a few years, or even months, before becoming outdated, pattern design time is a serious consideration. Furthermore, pattern designers’ compensation needs to be figured into the cost of shoes, so the less experienced the designer, the lower the cost that needs to be passed on to the customer.

Culturally, most people have been brainwashed into preferring pointy toed styles

For some reason, people in Western cultures associate pointy, heeled footwear with sophistication and elegance. Perhaps the roots of this date back to the days when nobility could afford to lounge around in impractical shoes, but peasants needed to wear broad shoes to work in the fields. Who knows.

Whatever the origins of the fashion, it is a persistent one: perversely, most people value the styles that are likely to ruin their feet and hence their health forever.

By the way, when we are thinking about how pointy shoes and boots overconstrain our toes, don’t forget socks. I have abandoned conventional socks: they force my big toe towards the center line of the foot just as a pointy-toed shoe does. Instead, I wear toe socks.

Problem 3. Heels vs bare feet

I’ve already written about how any kind of footwear heel is bad for feet, posture and health, so I won’t repeat myself here.

in short: lifting the heel stresses the feet and ankles unduly and put the whole body out of alignment. The higher the heel, the bigger the problem. I now avoid any kind of heel like the plague.

It’s pretty difficult to buy shoes that have no heel at all. Even apparently flat shoes such as athletic shoes often have hidden heel lift. A few companies do now make completely heel-less sandals, running shoes, and casual shoes. But good luck finding formal shoes without heels, let alone convincing your employer that they are suitable for work.

Why are heels so nearly universal? I can only conjecture some of the reasons.

A nifty noble foot from ~400 years ago. Doubtless the height of fashion for men at the time: James Hamilton, Earl of Arran, was aged 17 when this portrait was painted by Daniel Mijtens .

Signals of women’s gender and sexuality.

In general, the higher the heel, the more likely the wearer is female. Very few men’s styles today involve a heel higher than about 2cm (cowboy boots are the obvious exception).

Women’s footwear styles typically include higher and narrower/daintier heels than the equivalent styles for men. Our culture reinforces links between femininity and heel height. High heels are considered sexy for a reason: standing and walking in them draws attention to the size of a woman’s bottom and hips, as well as the shape of her bust and legs. The mincing, swaying gait they produce is considered seductive. The higher and narrower the heel, the harder it is to run and jump: draw your own conclusions about what this might signal whether subconsciously or deliberately.

Covert raised heels make men look taller

If high heels signal femininity, why do so many men’s styles still have heels? Why aren’t men’s shoes completely heel-less, for maximum contrast with women’s shoes?

Some men’s styles do indeed have small heels, or no heel at all. However, heels make a man look taller than he really is. Even in today’s societies where men don’t commonly fight each other hand-to-hand, a man’s height can still affect not just his career prospects but his likelihood of finding a female partner (so perhaps it’s unsurprising men often claim to be taller than they actually are).

Rather than eschewing heels altogether, most men’s footwear styles incorporate heels in ways that are considered manly. Heels are chunky and blocky, not delicate and fragile. Or they are included surreptitiously: the whole sole slopes upwards from the ball of the foot to the heel (look at men’s athletic shoes and sandals side-on), or the raised heel is included in hidden insoles/inserts rather than as a visible exterior feature.

By the middle of the 20th century, heels were the norm for everyone’s footwear in public. Even children’s shoes had heels. Photo from 1948 New York.

Resoling just the heel rather than the whole shoe

A few centuries ago, most roads were unpaved, and sidewalks almost non-existent. Contrast that with today, when many city dwellers may go weeks, months or even years without walking on anything except a hard surface such as concrete, tarmac or tile when outside. All these surfaces quickly wear down footwear soles, especially the heels in a person with a heel-strike gait.

It’s quicker and cheaper to replace the bottom of a built-up heel when it wears out than it is to replace the entire sole. Sadly, these days it’s often uneconomic to attempt to repair even the heels of most purchased shoes: it’s cheaper to throw them away and buy a new pair.

Problem 4. Inflexible soles vs flexible feet

Footwear soles provide protection and traction for our own soles. But stiff soles, and the toe spring that shoemakers include to try to make it easier to walk in them, are bad for feet. Basically, the stiffer the sole, the less able the foot is to work in the way it should.

For any given material such as leather or rubber, sole stiffness depends to some extent on its thickness. Despite being heavy, thick soles are often valued for the greater wear they can take before needing repair or replacement (think hiking boots). So do we simply need to choose footwear with thin soles, and just resign ourselves to replacing or repairing them more frequently? If only it were so straightforward.

The sole of a high heeled shoe is fashionably thin; it is also very stiff, thanks to a shank. (A clue to stiffness: spot the toe spring?)

Stiff soles help prevent the shoe twisting or folding unintentionally: a trait that shoemakers and wearers value, especially when the shoe has a heel. For reasons of design or economy, a shoemaker often wants to increase the stiffness of a sole without increasing its thickness. This is often done by including a shank, a length of stiff material (such as metal or plastic) that runs within the sole from the heel to the mid foot or even as far as the toes. Shanks help make heeled shoes possible.

Shanks of various materials and lengths are also routinely included in many other types of footwear, including hiking boots and men’s dress shoes. Even athletic shoes may include shanks or other measures to make the footwear reportedly more stable. This stability may help us in the short term, or we may like the look of shoes which use stiff soles to achieve a particular design effect like higher heels.

Just as we become conditioned to want pointy toes and heels, many of us think that stiff soles are the mark of a good shoe, when they are anything but. We also come to consider stiff-soled footwear to be normal because it’s what we are used to. However, our feet can suffer badly from being confined in footwear with inflexible soles for long periods: our muscles, joints and tendons deteriorate to the point where our feet have trouble working naturally. So when we try wearing shoes with thin, flexible soles, we think they are uncomfortable: because they are, at least in the short term, until our feet regain their natural capabilities.

Problem 5. Cushioning and orthotics

Modern footwear institutes a vicious circle:

- Thanks to years in shoes from early childhood, our feet have deformed to the point that they cannot work naturally to provide the stability or arch support or metatarsal cushioning or other function we need to be comfortable and avoid injury.

- So we are advised to wear shoes or inserts or orthotics which (claim to) provide the cushioning and support our feet can no longer provide for themselves. These aids may indeed help alleviate our symptoms in the short term …

- … but may actually cause further damage to our feet and health, by continuing to prevent our muscles, tendons and joints working as they should. Rinse and repeat.

Doubtless, many people do need artificial aids such as arch supports now, after their feet have been weakened and deformed after decades wearing conventional footwear.

And needing to accommodate a chunky orthotic may greatly limit the styles that one can wear. In fact, for some readers of this article, I suspect that "it’s hard to find nice shoes that can take my [insert name(s) of favored orthotic(s) here]" would be the first answer that comes to mind in response to the question posed by this article’s title.

In an ideal world, foot cushioning and orthotics would be recommended with the principal aim of healing the foot, so that their use can eventually be discontinued. But I have a suspicion that many of the folk who market foot comfort aids have a primary goal of maximizing profits, and I ask myself whether getting people to discontinue use of a product is compatible with this primary goal.

It’s worth considering whether transitioning to barefoot-style footwear (and foregoing any kind of footwear whenever possible) might help even more than these artificial aids, at least in the long term.

Note that I strongly believe that anyone thinking about abandoning professionally-recommended orthotics or other footwear should consult relevant medical professionals before doing so. Transitioning to minimalist or barefoot styles after years wearing conventional shoes is not something to be done abruptly or casually, even if one is lucky enough not to need any medically prescribed forms of foot support.

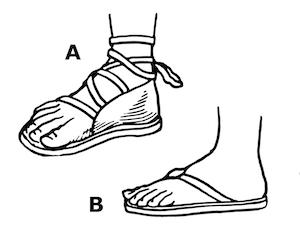

Two sandal styles. A is firmly attached to the foot at all times via straps. B (a flip-flop style) allows the heel to lift away from the sole.

Problem 6. Footwear that doesn’t attach properly to the foot

I want to end this post with some comments about the need to consider how the shoe is meant to actually stay on. Specifically, I want to talk about the extremes of the spectrum: shoes that keep slipping, and shoes that attach so tightly they stop the foot and/or ankle moving as it should. Both issues can cause long-term damage to feet, gait and posture; these changes in turn can make other footwear feel ill-fitting even when it is actually better for long-term foot health.

6.1. Likely to rub or slip off

Shoes slip for two reasons:

- The style doesn’t have adequate fastening to keep them tightly attached to the foot

- It has adequate fastening but it doesn’t fit the foot

In a way, the second of these is the simplest to identify, and the reason is related to that discussed in point (1) above. The shoemaker has made a shoe that would fit an imaginary foot nicely. But your real foot is not quite the same as that imaginary foot: it’s a bit shorter, or narrower somewhere, or your ankle bones are lower or higher, or whatever. So even though the buckles or straps or laces or other fastenings should in theory work well, the shoe doesn’t grip your foot as well as it should and part of your foot slips up and down or side-to-side. The rubbing can cause blisters or even raw patches. If you could persuade the shoemaker to use a last that was exactly the same shape as your foot, the shoe would stay on nicely.

It’s easier said than done to make a shoe that is neither too loose nor too tight during all kinds of locomotion. This sandal is nicely attached at the fore- and mid-foot, but the heel has too much lateral movement when running, despite the ankle strap.

But some styles don’t have good fastening: even if your foot magically matched the shoemaker’s last exactly, the shoe would slip off under some circumstances. Backless sandals and mules are the obvious examples of styles that are likely to slip.

When the shoe threatens to slip off, parts of your feet need to do extra work to keep it on. Perhaps your toes grip harder onto the sole. Or maybe you don’t move your ankles or legs in quite the same way as you would with a shoe that would stay on no matter how you moved. If you wear the shoe for many hours, this can cause undue fatigue and wear in parts of your feet, ankles or legs, even if you don’t notice it consciously. If you do feel tired or achy somewhere, you may not realize that feeling is related to your shoes: why would you connect knee or hip pain, for example, to your feet?

By now, you can probably guess that long-term use of footwear that threatens to slip off can cause long-lasting damage to feet as well as changes to habitual gait and posture. And these, in turn, can cause better fitting footwear to feel unnatural and uncomfortable.

6.2. Overly constricting

I’ve already mentioned the problem of tapering toe areas (point 2 above). But shoes can constrict feet in other ways. Perhaps they are too narrow across the ball of the foot. Or maybe it’s easy to lace them too tightly.

Whatever the reason, overly tight footwear that is worn for long periods can cause problems when you try to move to other styles. Muscles, joints and tendons can be affected by constricting footwear, so better styles don’t actually feel as comfortable as they should, at least in the short term. Maybe you even develop corns, calluses or other symptoms in response to the poor fit of your shoes, and these then affect how other styles feel.

In summary

Why can’t we find footwear to fit? Above, I outlined aspects of what I think the basic problem is: we don’t have footwear custom made for us from early childhood to suit the natural shape and movement of our feet. Instead, we wear shoes mass manufactured

I based the design for these slippers on old peasant shoes; the wide toes and completely flat, flexible soles are amazingly comfortable.

- for imaginary feet (shape and size doesn’t reflect our real feet)

- to have traits that are fashionable (e.g. tapering toes, raised heels, stiff soles, poor fastening systems),

- or that provide short-term comfort (e.g. cushioning) or increased wear (e.g. heavy soles).

Unless we are lucky, over the course of years such footwear deforms our feet, changes our gait and causes other (sometimes permanent) changes to our bodies. Not only are some of these changes painful in themselves, they can be further aggravated by traits of bad footwear: we can’t wear what we used to.

Furthermore, our bodies may be so affected by wearing bad shoes that good footwear actually feels uncomfortable, at least in the short term.

We may be able to slowly undo some of the damage by transitioning to less damaging footwear, but it may take months or years for our atrophied, worn, and over-/under-stretched muscles, joints and tendons/ligaments to adapt. If we are unlucky, bad footwear has caused permanent damage by the time we realize.

It’s currently very difficult to buy footwear that allow feet to move naturally. Instead, the economics of mass manufacturing and the perversities of fashion mean that almost every pair one can buy off-the-shelf will cause long-term problems even if they feel fairly comfortable in the short term. Indeed, this has been the case for many decades, and we have become conditioned both mentally and physically to expect traits in our footwear that will permanently damage our feet, and have knock-on effects on our wider health.

But the more of us who realize what a huge impact shoes can have on us, the greater the market for shoemakers who make footwear that provides every trait that shoes should ideally have: no heels or toe spring; flexible soles; an asymmetrical, roomy toe area; different length and width within a pair; etc.

In the meantime, I continue to make my own.